Demistifying HTTPS/SSL

January 08, 2019

First things first. If you have read anything about SSL, you have probably also seen the term TLS thrown in as well.

TLS is interchangeably used with SSL although they are not quite the same thing. TLS is the current version of the deprecated SSL secure network data transmission protocol. These days, when people refer to SSL in terms of HTTPS they are referring to TLS but SSL is the name that has stuck with the general community and so I will refer to the protocol as SSL throughout this post.

Note: This post is a conceptual explanation of SSL and the patterns around it. A practical post on how to implement SSL and its corresponding patterns in software will be addressed in a later article that will be linked here.

Why Use SSL?

Having SSL enabled on your website provides a big security boost. Any person familiar enough with how web applications work can track and spy on user information being sent to backend servers. Using SSL is a major step in obstructing unintended data monitoring. The main benefits of SSL certificates are:

- Encryption of data flow.

- Once a SSL connection is established, any corresponding data between the client and server is encrypted with a public key. Data sent from the client to the server can only be decrypted by a private asymmetric key (meaning the private key is different from the public key) on the server. This means that when a user submits their login information for example, only the receiving server can decrypt their credentials. An attacker may be able to view the data while it is in transit to the server, however, they will not be able to decrypt it therefore making it much less useful.

- Authentication

- Higher level SSL certificates like OV and EVs require the company or organization to be validated. This means that there was some kind of physical audit and process involving human interaction where the organization requesting the certificate is validated. This means these certificates give you confidence the domain is truly owned by the organization in question, and not by an imposter with malicious intent. EV level certificates even require the organization to have been operational for at least three years.

It should be noted that there are other benefits of using SSL like a boost in SEO ranking but encryption and authentication are the most crucial.

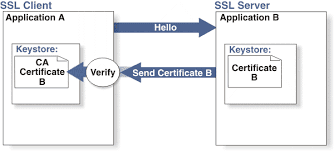

One Way SSL

In one way SSL, the client authenticates the server’s certificate. Once a connection is initiated, the server sends its certificate (a signed public key). The client then verifies the server’s certificate by determining if it is present in its truststore. If the certificate is found in its truststore, the server’s certificate is “trusted”. Once the certificate is trusted, all subsequent data exchanged between the client and server will be encrypted. The exchange is shown below:

Taken from ossmentor.com

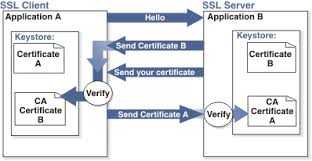

Two Way SSL

In two way SSL, the client and the server both authenticate each others certificates. The first steps are the same as one way ssl. After the client has authenticated the server’s certificate, the server sends a request for the client’s certificate. The client sends its certificate and the server validates it against its truststore. Only if both authentications succeed, then the connection will be established and any other subsequent data will be encrypted.

Taken from ossmentor.com

Browser Based SSL

How do these SSL patterns apply to a web browser? Well, every modern browser (i.e Chrome, Firefox etc) comes with a listed of CAs (Certificate Authorities) it trusts. When a CA issues a digital certificate, it has validated that the requester is who they claim to be. In this way, CAs act as trusted third parties. You can trust any digital certificate issued by a CA is authentic and valid.

Therefore, the list of CAs a browser ships with serves as its truststore. In one way SSL, when the browser initiates a SSL connection, and the server sends back its certificate, the browser verifies that the certificate has been issued by one of the CAs that it trusts. If so, the connection is made.

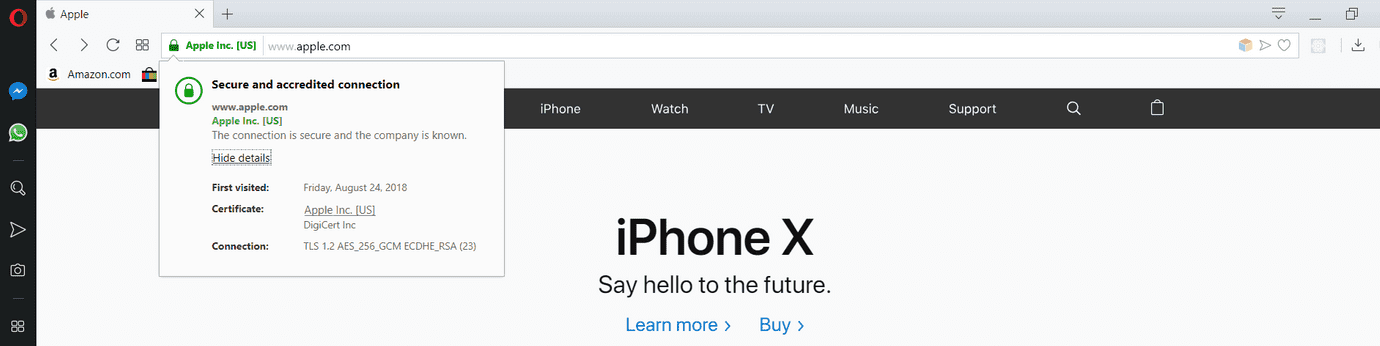

In two way SSL, the browser must also send its certificate to the server for server-side verification. If a website is SSL enabled, you can see its certificate by clicking on the green lock in the address bar. The location of the certificate will be slightly different for each browser. Here is a snapshot of Apple’s certificate in the Opera browser.

Taken from apple.com

You can see that it has been issued by DigiCert and if you click on the certificate link, you will be able to see more details about the certificate.

Server to Server SSL

From browser to server is not the only time SSL can be used. In the backend, server to server connections can also use SSL. For example, one API may need to call another API for data. Although this call may be in an internal network (therefore less vulnerable to snooping), SSL can be used for the data transfer.

In this case since the server requesting data will be acting as a client, the server at a minimum, for one way SSL, must be configured with an internal trust store (similar to the CAs browsers ship with). The trust store will need to be present on the server and configured appropriately to accept any expectant certificates. Loading the trust store can depend on many factors and is specific to each runtime. For example, Java has its cacerts file in the $JAVA_HOME/jre/lib/security/ folder which is used as the default truststore but the application code could also be configured to use a custom trust store file present as part of the source code.

For two way SSL, the trust and key (certificates) stores would need to configured or loaded by application code in both the server requesting the data, and the server responding with the data.

Note: Internal CAs are a common technique large organizations use to validate internal service to service calls.

SSL Certificates Using Proxy (Intermediary) Servers

Loading the certificates and truststores onto each server is repetitive and inflexible. If a group of servers share the same certificate, then the certificate must be loaded on all those servers. If the certificates expire, or the truststore needs to be updated, then those changes need to be replicated across all of the servers.

A better solution is to place the certificate on a proxy server and let that server handle the fulfilling the SSL handshake. A proxy server is simply a server that sits in front of your application. All requests corresponding to your application will first hit the proxy server and then be re-directed to the application server where your business logic is executed. The proxy server will contain the SSL certificate, so when a SSL connection is initiated, the proxy server will respond with its certificate to fulfill the SSL handshake. This way, any application server(s) behind the proxy have no need to load SSL configurations and the SSL configuration can be updated on the proxy without affecting the application server(s).

Example of proxy servers that provide this functionality is Nginx and Amazon’s ALB (Application Load Balancer).

Note: The technical term for this kind of proxy server is a ‘reverse-proxy’. A reverse-proxy can be used for more than just SSL. Because it sits in front of your application, it can do many things like filtering and blocking suspicious requests.

This was a conceptual explanation of SSL patterns. Article on practical implementations of these SSL patterns to come.